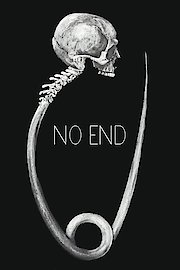

Watch No End

- NR

- 1985

- 1 hr 49 min

-

7.3 (5,931)

In the aftermath of the 1981 imposition of martial law in Poland, director Krzysztof Kieslowski crafted a haunting reflection on history, nationhood, and trauma with his 1985 film "No End." The film follows the lives of two women whose personal upheavals intersect in the aftermath of a young human rights lawyer's death. The first character we meet is Urszula (Grazyna Szapolowska), an emotionally distant journalist whose husband Jacek (Artur Barcis) died in the same airplane crash that killed the lawyer. Despite her distance from Jacek in life, Urszula's grief is palpable, and Szapolowska gives a terrific performance conveying the complex emotions she feels. Urszula's sadness is compounded by her parents' politics: they are fervent supporters of the regime that imprisoned and eventually killed Jacek.

The second woman is Anka (Maria Pakulnis), a similarly emotionally remote translator who is assigned to the murder trial of the two men accused of causing the crash. Anka is also grappling with unresolved trauma: her brother was picked up and disappeared by the authorities at the start of martial law. These two women begin to see the same therapist, Antek (Aleksander Bardini), who is himself struggling with his own disconnection from the world after the death of his wife.

As the film progresses, these three characters' lives start to intertwine in unexpected ways. Urszula begins to cover the trial in which Anka is translating, inexorably linking her grief and isolation to the larger political issues at play. Meanwhile, Antek contends with the various moral and ethical dilemmas that arise from Anka's involvement in the case.

As with Kieslowski's later works ("The Decalogue," "The Three Colors Trilogy"), "No End" is masterful in its use of symbolism and metaphor. The film's title is repeated throughout, often coming up in unexpected places (as in Antek's advice to a patient to "start over from a different ending"). The imagery of water is also central, from the airplane's crash into a lake to Urszula's many visits to a pool, to the repeated motif of the waves outside Anka's window.

Perhaps most noteworthy about "No End" is the way it approaches the subject of history. The film takes place in a time when Poland was transitioning from dictatorship to democracy, and Kieslowski's thoughtful approach to that transition is on full display. The characters are grappling with how to live with a traumatic past, how to understand the present, and what the future might hold. They are all living with no end in sight.

Overall, "No End" is a haunting, psychologically astute film that rewards close viewing. It is both a deeply personal reflection on grief and trauma and a larger commentary on how we live with the events that shape our world. Fans of Kieslowski's later works, particularly those interested in his preoccupations with ethics, morality, and choice, will find plenty to appreciate here.